ECHIZEN WASHI

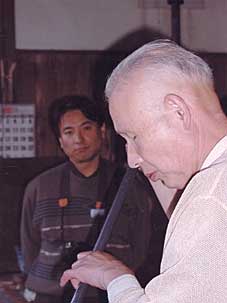

ICHIBEI IWANO / Living national treasure

100% mulberry paper made by traditional methods

-- buckwheat husk ash alkali bath, hand-beaten fibers, running cold-water wash, female gingko tree drying boards

Thanks to Japanese "living national treasure" Ichibei Iwano for allowing us to observe and record the main stages of papermaking from start to finish

"My aim is to create paper while preserving the mulberry fibers in their original state as much as possible"

Ichibei's strong commitment has been translated directly into the paper itself: simple and unadorned, gentle yet powerful washi. [Translator's note: it is recognized that the fibers of various types of paper mulberry are used to make paper by hand not only in Japan, but also in China and Korea. However, it is to be expected that local variations in materials and methods will produce different results; therefore the Japanese term "washi" -- literally, "Japanese paper" -- is used.]

Fibers are cooked in an alkali bath made from ashes of the best grade of soba husks from Nasu, TochigiPrefecture, and then beaten . . . no effort is spared in realizing the best paper possible.

Since only natural vegetable matter is used, this paper is ideal for dyeing (stains such as indigo dye and colcothar dye). Because it is free of impurities (no kaolin is added), only pure Japanese paper mulberry fibers (100% Nasu paper mulberry, Broussonetia kazinoki x papyrifera, hereinafter referred to only as "mulberry") and zero chemical agents (no caustic potash soda or soda ash) are used, it should take on colors very well. Ichibei believes there are people looking for paper like this. He says users can expect the paper to take on colors wonderfully.

This superb paper represents the ultimate uncompromising mulberry paper, the pride of the washi made in the Echizen region of Japan.

Neri Tororoaoi Noriutsugi

Ichibei's "naginata beater"

September 27, 2001, clear skies

We start by making the alkali bath.

|

Although I had heard we would set up from the afternoon, |

|

|

Looking outside I notice a tall kettle . . . This tall kettle has an important role to play today.

|

|

|

Inside the kettle can be sen Nasu mulberry bark, waiting for tomorrow's cooking. By the way, this kettle is cast and cost 132,000 yen when it was purchased back in 1975!

|

|

|

For the time being, let's put in some water and let the bark sit overnight. | |

|

Now what's he dragging over here in that large paper bag? | |

|

It's ash from buckwheat husks. Written right there in plain Japanese

|

|

|

Very beautifully finished. | |

|

This was buckwheat husk ash was made by an old grandmother who ran it through a sieve to make a very even, high quality ash. It was purchased in 1987. By the way, it cost 20,000 yen to make this buckwheat husk ash. (Ichibei has a good memory for numbers.) Making it is really a lot of hard work.

|

|

|

Now Jun Iwano makes a beeline for the hill out in back . . . He has come to collect cedar needles, and since I'm here too, I also lend a hand . . .

|

|

|

So in effect he is trimming the cedar tree. What are they going to do with these?

|

|

|

Now they are ready to change the setup of the factory Normally Ichibei cooks the Nasu mulberry bark in soda ash. But for this batch of paper he wanted to use an absolute minimum of chemical agents, so he shall cook using buckwheat husk ash, which has an especially strongly alkalinity among ashes. As a result the setup procedure is more extensive than usual

|

|

|

By the way, when cooking with buckwheat husk ash, the ratio of ash needs to be 60% of the dry weight of the mulberry. In the case of soda ash, the ratio is 12%.

|

|

|

Now the cedar needles are washed clean. | |

|

Hey, they are putting these into the tall kettle! By the way, this tall kettle is an all stainless steel order-made item, purchased by Ichibei's father (who was the family's eighth-generation paper maker and also used the name Ichibei, and was also a living national treasure) about 40 years ago At that time it cost about 50,000 yen.It was purchased for only one purpose -- to make the alkali bath, and has not seen much use. In fact, this was the first time to use it in about a decade.

|

|

|

Stay tuned . . . I exceeded my digital camera's storage capacity, so we have to wait for the photos to come back from the photo lab.

|

||

8 AM, September 28, 2001, clear skie

|

At 8 AM, it is another day of good weather. By the time I reached the kettle, the kettle was already at a boil. The mulberry bark awaiting cooking is temporarily removed to a tub in the background. That tub too is all stainless steel. |

|

|

The moment of truth is at hand ! Boiling water is poured into the tall kettle. Will all go well?

|

|

|

And as soon as the hot water was put in, a bubbling cooking sound could be heard coming from inside the pot. And then it started to foam . . . will the alkali bath be a success?

|

|

|

Let's twist the cock and check. Wow! A dark black alkali comes out.

|

|

|

Let's check it with litmus paper while we're at it. | |

|

Yep, that's definitely an alkaline liquid. | |

|

Okay, we're all ready ! The color is black but it is actually a very clean liquid free of impurities.

|

|

|

Temporarily the boiling water needs to be removed from the kettle, so the alkali is also temporarily moved to buckets.

|

|

|

All the hot water remaining in the kettle has been removed to the buckets. | |

|

Finally the cock is twisted and the kettle filled with alkali. | |

|

It required more buckets than I had expected. | |

|

Initially black, the color of the alkali gradually lightened to the color of a cola drink and then to the color of light soy sauce. | |

|

Finally the kettle is surrounded by firewood. Burn, baby, burn !

|

|

11 AM, September 28, 2001, clear skies

|

Okey-dokey, as the kettle has come to a boil, it is time to cook the mulberry bark.

|

|

|

In the morning they were already lightly cooked once, and this is how they look. This time we are cooking a dry weight of 30 kilograms of mulberry bark.

|

|

|

It has come to a bubbling boil. | |

|

After the tall kettle has finished its job superbly, the ash has hardened. The ash and the chaff hidden below it were dumped as-is into the garden plot behind the tall kettle, where they became fertilizer.

|

|

|

And before the serious boiling begins . . . There is the job of loosening the mulberry.

|

|

|

All preparations are finally ready. | |

|

I'm told this is cooking very well. | |

|

Does it look delicious? From this point onward, every 50 minutes the contents of the kettle are flipped upside down . . . while repeating that, cooking goes on for four hours.

|

|

|

The view facing the hill behind the kettle hut. It sure is peaceful . . .

|

|

2 PM, September 28, 2001,clear skies

|

Okay, the cooking process has been successfully completed.

|

|

|

The fire under the kettle is extinguished and the mulberry is allowed to steep. | |

|

With the kettle covered as shown in the photo, the mulberry steeps for two hours. Patience, patience . . .

|

|

4 PM, September 28, 2001,clear skie

|

As the sun started to get low in the sky, around 4 PM, the steeping was finally finished. | |

|

Go to it, Jun ! There is still one more job at this stage.

|

|

|

The steeped mulberry bark is moved to a stainless tub . . . this to is a special-order item with an upraised bottom and designed to allow fluid that drains off to flow back into the kettle. This was built rather recently, in 1998, at a cost of 70,000 yen

|

|

|

Hasn't is boiled up beautifully? The working procedures are exactly the same even when regular soda ash is used. -- Except for the dark color of the fluid . . .

|

|

|

Notice how the fibers separate. Tomorrow is removal of impurities . . .

|

|

11 AM, September 29, 2001, clear skies again

|

Today is supposed to be a day for removing impurities from yesterday's cooked mulberry fiber The whole family helps out -- the grandmother, Mrs. Iwano, Ichibei, and Jun. Even with all these people helping, the procedure takes several days. (Removing of impurities: this is important because any impurities remaining at this stage will wind up in the finished paper. This painstaking work is conducted in silence, with total concentration.)

|

|

|

Ichibei points out to me the difference in appearance between mulberry cooked with soda ash (on the right, whitish) and |

|

|

"This is the way it was always done in the old days"

|

|

|

In this way, one strand at a time, the fibers are exposed to light and water in the relentless search for even the smallest particles of impurity. | |

|

. . . and still the cleaning process goes on, silently . . . silently. | |

| The cleaning process started on Saturday. Monday will see the making of what is called the "neri" -- a mucilaginous liquid that is an original Japanese development in Oriental mulberry paper making, together with the "nagashizuki" method of papermaking, and which helps to keep the paper fibers floating in the vat and on the bamboo framed screen (sukiketa) for a long time. | ||

10 AM, October 1, 2001, light rain gradually turning to clear skies

|

It finally started to rain. The view looking back toward the hillside behind the washing hut

|

|

|

As shown here, water flowing through a gulley in the hill out in back is piped to the washing hut and water is pooled here. |

|

|

These roots are washed for a full day in this running stream water. This is a plant known as tororo-aoi (Abelmoschus manihot) and this is what they look like after being washed since yesterday. Regrettably, the rain causes turbidity in the water flowing into the holding tank.

|

|

|

Anyway, they are ready to come out of the water ! | |

|

Jun has started to pound on the roots with a wooden mallet. This was a first for me -- I had never seen this before and had simply assumed that the "neri" was made using a machine of some sort. I wasn't anticipating scene like this. Amazing !

|

|

|

Ichibei informs me that too-large roots are no good. If the roots are too large, the skin on the roots splits open as soon as you start pounding with the wooden mallet, which apparently is not a good thing. The entire length of each root is carefully pounded, all the way to the slender tips. By the way, this tororo-aoi comes from GunmaPrefecture

|

|

|

In this way, it is beaten flat. However, beating it too much is not good either. The need to avoid over-beating is one reason why wooden mallets are used instead of a machine.

|

|

|

One more time, back into the running stream water for another wash. Taking on water is what gives tororo-aoi its characteristic mucilaginous qualities.

|

|

|

And here is yet another type of "neri" -- made from bark . . . Nori-utsugi, Hydrangea paniculata Siebold. This is from Hokkaido, where it is known as "sabita" and is harvested around July-August.It can also be obtained from the Hizen region, where it is known as "nire," but the product from Hokkaido is better.

|

|

|

As you can see, it is a single sheet of inner bark from a tree. It is less powerfully sticky than tororo-aoi. | |

|

"Neri" is always better when prepared after a little time has passed rather than using immediately after manipulation of the ingredients. "Tororo-aoi is too sticky and the fibers don't expand. Using nori-utsugi gives fully expanded fibers that make the paper easier to scoop." I can see that Ichibei has a strong commitment to excellence even regarding "neri."Ichibei makes "neri" by mixing tororo-aoi and nori-utsugi together.

|

|

|

Here is the actual stream that I have been mentioning. Water is piped from here to the work area. While we were making the "neri," the sky cleared up again. (I have a feeling that something good is going to happen ! )

|

|

|

The Echizen region does not have any really large mountains or streams, but it does have a profusion of springs. |

||

A brief detour: the flowers and seeds of the tororo-aoi plant -- Utatsu Crafts Hall

11 AM, October 2, 2001, clear skies again

|

I was told that I should go take a look at the flowering tororo-aoi plant in front of the Utatsu Crafts Hall. Regrettably the flowering had almost completely finished, with just a tiny bit left on top; however there were some impressive fruit forming. |

|

|

Note how vigorously it bears fruit. It's too bad I couldn't see the flowers in full bloom !

|

|

10 AM, October 4, 2001, cloudy

|

And now begins the loosening of the fiber in the bark. Ichibei quipped, "We got lucky -- it came out well!"In fact it had cooked up extremely well and the separation of the fibers was excellent.

|

|

|

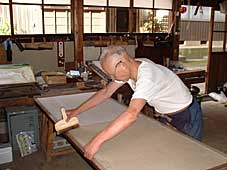

We start by placing the mass of cooked inner bark, with all the particulate impurities removed, atop the work bench. First we thoroughly press out the water . . .

|

|

|

This work bench is made of zelkova wood, and a maple mallet is used to pound the mulberry bark.

|

|

|

In this manner, all the mulberry bark is beaten by hand.

|

|

|

Usually, after about four "makuri," the material is taken to the beater (beating machine); however, if one was to do it all by hand, it would take 10 "makuri," which would take a full two hours of constant beating. | |

|

One sign of a mature craftsman in this field is the ability to flail the mallet down flat (horizontally) across the entire batch, as shown in this photo. | |

|

Here is mulberry that has just been beaten by hand. | |

|

Here is how it looks when held up to the light. Am I the only one who gets the impression that it's somehow alive?

|

|

Afternoon, October 3, 2001, clear skie

|

After hand beating, the material is put into the "'naginata' beater."

|

|

|

However, they will never abdicate responsibility to a machine. |

|

|

"How is that? -- beautifully separated fibers, are they not?" "It went very well . . . " "Hey, we got lucky . . . " (since the cooking in buckwheat husk ash went so well)Normally the naginata beater is used for about eight minutes; however, this time everything went smoothly so four minutes in the beater was sufficient.

|

|

|

The material from the beater is strained . . . At the bottom of this blue container is a fine screen designed to allow the water to drain off. "Hmm . . . it feels kind of slippery [even though it is mulberry]. Who knows, maybe it will turn out like "ganpi"* or "mitsumata"** paper . . . " (* Diplomorpha sikokiana Nakai, family Thymelaeaceae) (** Edgeworthia papyrifera Siebold et Zuccarini, family Thymelaeaceae)

|

|

|

Into the bucket it goes. Tomorrow will be the elaborate washing-out process known as "kamidashi."

|

|

|

Meanwhile, Jun is already preparing for the next batch of papermaking. Before cooking the mulberry, it is necessary to remove as much dirt and other impurities as possible, which he is doing here. At every stage, this whole business requires huge amounts of determination and patience.

|

|

|

By the way, the tororo-aoi beaten the other day at the washing hut has become really mucilaginous -- very tenacious slime. Now we're ready !

|

|

Addendum . . . Ichibei's "naginata beater"

|

Here is Ichibei's "naginata beater." These look like sharp scimitar blades; but in fact they are not sharp at all. These are used to separate the mulberry fibers from each other. They do not have the ability to cut the fibers. These blades are extremely long, and were made to order.

|

|

|

For comparison, here is what the blades of a typical "naginata beater" look like.

|

8:30 AM, October 5, 2001, cloudy

|

Here Jun is in the midst of the climactic process for preparing the material for papermaking. Today is "kamidashi" day. All these thoroughly separated mulberry fibers need to be washed in the water of the stream.

|

|

|

The fibers are repeatedly stirred by hand, to thoroughly wash the starch out of the mulberry fibers. This lengthy, painstaking washing process with large amounts of clean, cold stream water is one of the reasons for the extreme long-term stability of this paper and resistance to insects: you eliminate every trace of whatever is not mulberry fiber.

|

|

|

Every corner is repeatedly stirred by hand, filled with determination to thoroughly rinse every last fiber. In the cold winter months this is an especially unpleasant job.

|

|

|

The fibers having gone through the "kamidashi" process look like a row of lumps of dough or rice dumplings. | |

|

"So, what are you going to name this paper?" Jun answers, "Oh, I dunno . . . maybe 'amber ancient paper' . . . " The painstaking washing goes on and on . . .

|

|

|

Before (below) and after (above) the "kamidashi" process What a difference in color ! -- and all due to washing with water. It's readily apparent what an important step this is. By the way, when caustic soda is used, small amounts of impurities are bleached, so this "kamidashi" process is not needed.Perhaps "kamidashi" is one way to distinguish between the hard-core uncompromising craftsmen and the compromisers?

|

|

|

*** Time for champagne and fireworks ! *** It sure was a long road just to get this far . . . But the most important steps in our journey are still ahead of us.

|

||

|

Ichibei quipped, “Mr. Sugihara, by now you must know enough about papermaking to be able to make it yourself . . . " He has been scooping the fiber solution and making sheets of paper since 6 AM this morning.

|

|

|

If he sees any stray clump of fibers or any impurities, he immediately removes the offending matter with a needle. The part o the paper that faces the bamboo-netted framed screen will become the bottom side of the paper. (At least, that's true in Mr. Iwano's case.) "Since there is no kaolin, you can see the fibers very well . . . "

|

|

|

Gradually the paper grows in thickness. Splash, splash, splash . . . the p formsrepeated scooping creates a nimble rhythm. In Ichibei's case, the final scoo the front face of the paper. The surface contacting the bamboo-netted framed screen becomes the rear (bottom) face. (In contrast, "Torinokogami" made by Mr. Hirasaburo or Mr. Yanagise has the texture of the bamboo-netted framed screen applied as-is to the boards for drying. The reverse is the case when a "cloud texture" is deliberately sought.) In the case of "torinokogami," the bamboo-netted framed screen texture provides the front of the paperand with "hosho" type papers the opposite face becomes the front of the paper.

|

|

|

The completed paper is stacked up in order. After all these long years of experience, there is not a single wasted movement. It is almost like watching a sort of dance. |

|

|

I'm advised that if I visit various papermakers, I should be sure to note whether they have two different bamboo-netted framed screens. Ichibei quips, only partially in jest, "Paper doesn't sell like it used to . . . maybe I'll have to give up papermaking . . ." Good technologies and the men who take the trouble to master those technologies can only exist through consumers' patronage.That is one of the tough realities of any traditional craftsman's technology

|

|

|

With brisk motions, the mulberry fibers are formed into paper. It is amazing how washi is produced this way out of just water and other natural materials.

|

|

|

As can be seen in the photo, while scooping fiber, the other bamboo-netted framed screen is kept lying down flat. If the bamboo-netted framed screen is lifted up immediately, air bubbles form and inferior paper will result.The use of two bamboo-netted framed screens is one aspect of a good papermaker's commitment to excellence.

|

|

8 AM, October 6, 2001, clear and sunny

|

Good morning !

|

|

|

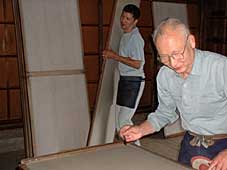

"We've been applying paper to the boards since early in the morning." | |

|

One sheet at a time is carefully peeled from the "shitogami," which might be translated as "paper on the bed." |

|

|

This time we had the paper made in one of the traditional Japanese standard paper size formats, the "kikuban" format measuring about 94 x 64 cm, so the boards used are also large. This is the largest board size that Mr. Iwano can scoop. By the way, these boards are made from the wood of female gingko trees. Gingko wood is free from traces of the annual growth rings, so the surface is smooth and produces paper with a beautiful surface texture.

|

|

|

Gingko trees are precious and unless they are large, boards must be joined, and of course the joints are noticeable in the paper. As a result, large gingko boards free from joints are highly valuable.

|

|

|

"After you think you have got the paper applied just right to the board, and everything looks just right, you back over it one more time, lightly . . . that's one secret to making good paper." | |

|

In the past, large boards like this were dried outside in the sun . . . "Here, try picking up one of these . . . it's not easy carrying them outside." When I lifted up one of the boards, I was surprised by how heavy it was. The boards were heavier and thicker than I had imagined, and moving them around is a lot of work.

|

|

|

The boards with paper applied to both sides are carried to and placed in a small room called a "muro" for drying. | |

4 PM, October 6, 2001, clear and sunny

|

Well, how well have they dried? | |

|

"We'll dry one more time after this, so all the drying will be finished this evening around 8 PM. | |

|

The dry paper is removed on sheet at a time from the boards . . . | |

|

Jun has a serious expression as he examines the finished paper. | |

|

Wow. |

|

|

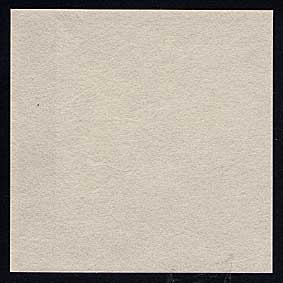

This paper has a wonderful warmth. | |

|

And it also has a lot of sheen This paper has a very gentle finish.

|

|

|

This work continued until sundown . . . and even after sundown. Than you very much

|

|

9 AM, October 17, 2001, cloudy

|

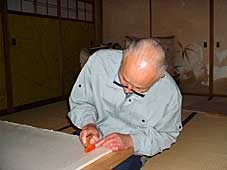

Finally we have arrived at the day when all is finished safely. Each sheet is carefully inspected.

|

|

|

"This here is not quite right . . . " he says while pointing with his finger. | |

|

It does indeed seem to be slightly thinner than the surroundings. 210 sheets made it through the rigorous inspection to qualify as his finished products

|

|

|

100 sheets were stamped on the back side with his seal bearing the Chinese characters for Ichibei Iwano. The remaining 110 sheets were left plain, unstamped. (Sometimes that might be preferable for painting pictures or additional processing . . . )

|

|

10 AM, October 17, 2001, cloudy

|

And then I had one more request to make . . . would he kindly make some "momigami" (wrinked and creased paper)? | |

|

Ichibei's pure washi, after crumpling to soften it, is used for wiping high-grade Japanese swords. It occurred to me that the paper I asked him to make this time might be used for such purposes, so I deliberately arranged to have the paper made slightly on the thin side.

|

|

|

So he crumpled, and crumpled, and crumpled yet again . . . | |

* Here it is ! Completed "momigami" ! *

* 20,000.00 yen per sheet *

| * Product No.: SH-ICHIBEI-900x600 * Unit price: 20,000.00 yen per sheet ‘approx. 960x660mm) * Thickness: about 210 micrometer * Weight: about 37 g * Living national treasure Ichibei Iwano's hand-made "Hosho" paper |

This is traditional Echizen "kisu" (unprocessed) Hosho paper. |

A sheet of paper made by a living national treasure of Japan This superb paper represents the ultimate crystallization of Ichibei Iwano's desire to take what originally came into the world as mulberry fibers and transform them, with the absolute minimum of processing, into paper. His insistence on the old-time methods of manufacturing, with his direct hands-on involvement at every stage, and his patient, determined commitment to excellence and consistent quality has resulted in these superb papers. So simple and plain, so unassuming and understated, so gentle and yet immensely powerful, this paper has a truly profound presence. It represents the highest grade of mulberry paper, the pride of the centuries-old Echizen washi tradition. |

|

"This paper is extremely soft. |

||

|

|

||

|

Here is a close-up of the paper after being luxuriously crumpled. | ||

|

It has a wonderful luster. And the softness after crumpling is indescribable. This paper is 100% pure, and has no anti-stain finish added. If you wanted to use this seriously for clothing manufacture, it should have "konnyaku" (amorphophallus konjac) starch applied before crumpling; when this is kneaded in, it can make lightweight, durable paper clothing. |

||

|

This sheet was crumpled wet after application of "konnyaku" starch. Ichibei's already strong, supple Hosho paper takes on even greater strength . . . it truly feels like a material that transcends paper.

|

|

"Don't call me a 'national treasure'; I'm an artisan"

"Don't call me a 'legend' -- I'm still alive"

Just as the previous generation (8th generation) Ichibei Iwano, who was also designated a living national treasure, used to say, Ichibei believes it is not the technique of the artisan that makes good paper, but rather it is the water that does the work . . .

Ichibei, a man of quiet humility, gently insists on that point. Ichibei strives for simplicity and naturalness -- to take the fibers born of the mulberry plant and transform them as-is into paper.

It seems so simple when he does it, but it is in fact a great work to produce a single sheet of this "perfect" paper. And Ichibei does this every day, in his characteristically unassuming fashion.

There is a papermaking song in the Echizen region with words that may be translated as, "It's our God-given task, from one generation to the next -- father, son, grandson making paper . . . pure hearts, pure water go into the sheets, drying into the whiteness of the Hosho paper . . . "

Special thanks

Christopher Witmer

This page is maintained by Yoshinao SUGIHARA.

Washi Sommelier and Washi Curator.

SUGIHARA WASHIPAPER, INC.

e-mail:sugihara@washiya.com

http://www.washiya.com/

Fax 81-778-42-0144

Please contact me anything about mentions on this page, questions, opinions, etc.

Also it's more than welcome to have Links to your home pages. All right reserved Copyright(C)Yoshinao SUGIHARA

www.washiya.com